What I Learned: Semester Three

Recapping semester three, the most rewarding and enlightening, yet.

It’s said that designers are great at conversation at cocktail parties because we know a little bit about many things because the work we do calls on us to interact with many industries and products. In my case, I can talk about aircraft racing engines, hearts of palm, the Christian liturgical calendar, residential fencing, at-home health care, and elementary school textbooks to name a few. But at the outset of this semester if you would have come up to me at a party and asked me about design research I would have been fumbling for words. Granted, after a semester of work I am still developing my own definition and getting my bearings but the past four months has allowed me to conclude two things:

- Design Research is what I was made to do.

- Every interaction, thought, relationship, product, value and generalization has been put on notice: I will never see the world the same way again.

This “What I Learned” is hardly comprehensive: I would wear out a keyboard typing all of the things I discovered. So, in the interest of brevity (and with hopes that you will actually read all the way through to the end) here are the highlights:

Design Research Theory

Keith Owens

“Theory” was a scary word before August 25 when classes started. It was still a scary word a few weeks in. But over time I learned to embrace Design Research Theory with open arms and now I’m at that awkward spot where we’ve hugged too long to be just friends anymore… and I’m okay with that. Let’s just say, “we’re close.”

Theory is just a tool for making sense of the world. I liken it to a set of binoculars you can use to see further: depending on how far you want to see, you pull out a different set. But the looking isn’t the fun part. I have learned that theory has significant value for designers and especially design researchers. If you’re a practicing designer about to scoff at me for waxing academic, let me preface my jaunt with a question that I hope will pique your interest:

If there was a tool that could help you discover new creative, organizational, commercial, and production possibilities, would you use it?

Well, theory is that tool.

Many of the theories we studied, like Bruno Latour’s Actor Network Theory, Terrence Love’s Meta-theoretical Structure for Design Theory, and writings on Critical Design projects like those of Dunne and Raby gave me frameworks from which to explore the relationships between ideas, products, and values. These theories may have daunting names but at their most basic level, they are just tools to assist those using them to determine patterns and to highlight relationships. In all, I learned that through using theories I can gain great insight into the way things are and why they’re that way, offering a great opportunity to make more informed decisions in the design process. The set of theoretical tools I have begun to explore has allowed me to identify connections and interactions that take place between and within environments, products, organizations, and systems. From my experience, I believe that as designers, our work will be more effective if we examine interactions (and potential interactions) more clearly and theory is a powerful tool in doing just that.

Design Research Theory also gave me context for my career and life-work. In short, I discovered the why of my design work. I’ve been doing design and solving problems professionally for over 13 years but exploring different design theories on design knowledge itself, design processes, and the roles design plays gave my daily work a name. All these years I have been doing the work but have never paid attention to how or why I’ve done it. But as I read through and studied the work of a variety of researchers I learned that I am not alone in the big scheme of design. I learned that the processes and methods I have learned and have been using to create have names, have been documented, have been proven to work, and have extensions that I am starting to explore and apply in my design and research work.

Design Research Theory challenged me in many ways, but maybe the greatest is the simple statement that the problems we define are more important than the solutions at which we arrive. I learned the importance (and fun!) of problem formulation. As designers, our first and most important work is to define the problem properly. Think about it, if we solve the wrong problem, our solution may be brilliant (functionally, aesthetically) but will be pointless because we missed solving what really needed to be solved. I learned that, whether it’s in design practice or in design research, taking the time to define the correct problem is essential. Thanks to Design Research Theory, I am far more interested in problems, then solutions.

Aha!

There’s nothing “theoretical” about the study and use of theory.

Design Research Methods

Michael Gibson

While the “doing” of the Methods course was more like what I’m used to in my study of Anthropology and in my own design practice, there was plenty of room for discovery, especially in the work of learning a new language. Terms like “validity,” “causality,” “literature review,” “longitudinal study,” and “basic research,” stormed into my Thursday night vernacular and have since spread into my everyday work.

Learning methods for design research, their benefits and uses (and pitfalls!) gave me the beginnings of a set of tools I will now use to put the theories I discover and formulate into action. Among scientific research methods, I also learned specific methods that are effective in design research. While many of these methods are helpful in conducting research and gathering data, my greatest discovery was that, through the use of methods in research, new connections, ideas, and relationships can be discovered. Sneaky, sneaky methods.

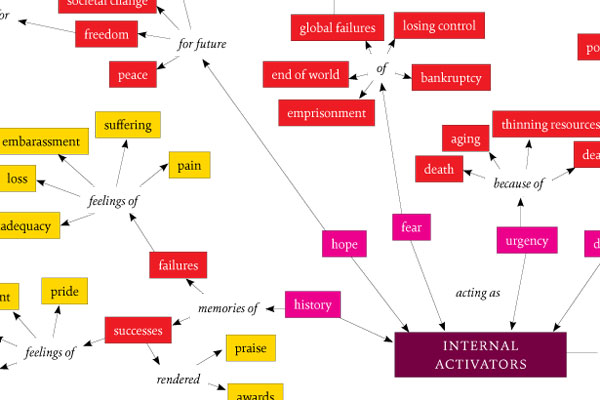

One method we explored over the semester was concept mapping. At first blush I was skeptical. I mean, I’ve researched, developed concepts for, and designed many information design projects and how much different could a concept map really be? In case you’re curious my words were slightly sweet, tasting like apple and cardamom with a slightly woody finish.

The power of concept mapping is in its ability to force one to stop and examine the next steps. In that, it’s kinda like a Choose Your Own Adventure book. By creating a node then thinking about possible steps that come from that nodal decision step and mapping out all of the possibilities, you limit yourself to the decision steps that are directly connected to the present step, removing thinking about the entire problem and focusing on problem-solving on just the immediate step. As one repeats the process it becomes clear that:

- one problem can trigger many new problems

- problems often bring with them seemingly infinite variables

- you’re going to need a bigger boat (methods and theory)

I never expected that I would discover research opportunities through doing. But through the semester I augmented my collection of theory binoculars with a toolkit of methods. I can’t imagine one without the other and I never imagined each could be used to both do and discover. Coming out of the semester, I have a view of the research landscape that was previously nonexistent.

Aha

A research method is only “good” if you know how to properly use it.

Seminar in 20th and 21st Century Art

Dr. Jennifer Way

After coming off of an enlightening semester-long study of Modernism and Modernity last semester with Dr. Way I was eager to jump in again for another foray into modern art. Looking back at my recap from semester two, my “a ha!” for the course was: “The advance of technology affects everything.” Considering Fall 2011’s topic for this Art History Seminar was Art and Technology, I believe a successful segue has been completed.

Technology is an odd thing: always present, a driving force in society, revered and hated, foreign and familiar but so difficult to define. I have found that too often, the use of the word “technology” triggers thoughts of all things digital but at its core technology is really just science put to use. Through my study this semester I am convinced that any study of technology must be done in context: the environment in which a technology is used must always be considered. I guess I always knew this, but as I waded into the waters of this course the importance of keeping that concept in the front of my mind continued to surface.

Think about it: a printing press, a calculator, the mapping of the human genome are all manifestations of technology just in different time periods having different influences during those times. Technology is such a contemporary, here-and-now phenomenon that examining the technology plus that which surrounds it is important in gaining an accurate, unbiased view of that very technology. The act of examining the roles of art and technology taught me the importance of removing myself from my place in a contemporary culture so I can place myself in the “shoes” of those whose views of technology are not my own, whether they be from a different time period, geographic place, societal position, gender, language or technical ability level.

To my 96-year-old grandmother, the advent of radio was likely just as revolutionary as the emergence of the internet was to me. But at the same time, both of our past experiences and perspectives likely colored our views of the respective technological advances in different ways. Our conceptions and misconceptions colored our reactions the new technologies. In this reasoning, I found the most important lesson I discovered this semester: the value and importance of context.

Over the semester my classmates and I were introduced to various pieces of art. Pieces like Vertov’s 1929 film, Man With a Movie Camera, the E.A.T. Pepsi Pavilion from Expo ’70 in Osaka, Japan, the seemingly design research-like work of Stephen Willats and Wafaa Bilal’s challenging work, Domestic Tension on the power of technology to dehumanize raised my awareness of art’s value in challenging what technology is and what it can do to and in society. We read work by writers and cultural critics like Marshall McLuhan, Raymond Williams, and Judy Wajcman, highlighting issues where technology, culture, and gender collide. I discovered scholars like Nicolas Bourriaud whose writings on art and its impact on and role in society elevated art’s relevance as a discussion and I delved ever-so-briefly into issues of bioinformatics, human genome mapping, and ethics in bio-art by Eugene Thacker. I was inundated with ideas from all sides and was challenged with many contextual perspectives. And after all of the reading, viewing, thinking, and discussing I arrived at one powerful conclusion and one sad realization:

Powerful Conclusion:

Art and artists are raising some very important, poignant, powerful, and thought-provoking issues in ways few will, can, or has.

Sad Realization:

Either not enough people are listening or the art isn’t reaching the people or no one is taking the time to care (or all three).

I know that’s a glaring and gross generalization (and my professors will likely join Bruno Latour in hacking my site to also berate me for making it) but I state it only because this semester I have gained such a respect for modern art as an important means of societal commentary with regard to technology. I think it’s easy to discard art as an “individual activity” that’s only about expression and aesthetics, but the way art was framed (I know, haha) this semester allowed me to see art and artists’ value in sparking discussion as a reflection of contemporary cultural practices. The issues are there. Why aren’t more people talking about them and doing something about it?

Aha

The humanities and the sciences need one another, desperately. They can solve more together than they can, apart.

Context

This semester was a turning point. I believe I learned as much about myself as I did the content covered in my classes and all of it amounted to one thing: context.

I discovered the importance of context: knowing where you are, what’s around you, where you’ve come from, and the effects of your environment on you.

I gained context: that design research is what I was made to do, how just studying problems or just formulating problems or just solving problems is not enough. I want to do all three.

I better understand context: by looking through a theoretical lens, a methodological lens, and a historical lens, I understand that when they converge, the position is triangulated and context is gained.

Up Next

I’m full of ideas. I’m full of passion. I’m full of Christmas overeating. But need to strengthen my reasoning and writing abilities in the “off-season” so I am reading. A lot. Over the break, my focus will be on reading books on classical rhetoric, critical thinking, and philosophy in advance of a spring semester filled with writing, research, and more art history. I’m at the halfway point now and feel that, equipped with some clarity gained from the past three semesters, new discoveries await.

Be the First to Comment