What I Learned: Semester Two

A semester’s worth of lessons in one blog post with discoveries in design pedagogy and art history.

With the conclusion of the spring semester, I’m officially one-third of the way through my MFA coursework. This semester could easily be considered the “teaching” semester: all of my classes had something to do with pedagogy, which focused my thinking and my work on one topic. I enjoyed the ability to hone in on one main area of study; however, semester two’s out-of-class lessons were a little more broad in nature, like:

- Developing pneumonia during a semester will set you back the entire period.

- The spring semester is tougher than fall: you’re not fully recovered from the first half but you still have to maintain the same intensity.

- “Snowmageddon:” our week of no classes due to snow and ice here in Texas made a mess of class schedules.

- When you love what you’re learning, it doesn’t feel like work (unless it’s 3 a.m. when you’re doing it, and then it most definitely feels like work).

So here’s what I learned in the second semester:

Design Pedagogy

Eric Ligon

At the outset of my academic career at UNT I looked through the coursework and thought the word “pedagogy” was a bunch of fancy gibberish. I mean, why not just say “teaching” and be done with it? I learned from experience that there is no better word as there’s a lot more to teaching than just teaching.

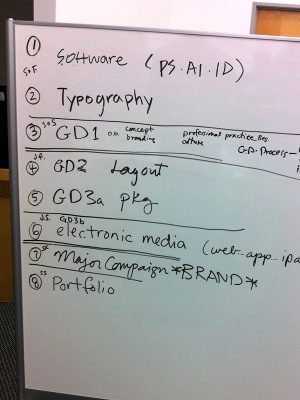

Design Pedagogy should be a required course for anyone aspiring to teach in higher education. This course required my classmates and me to examine all of the skills a student should possess by the time they graduate from an undergraduate design program. We created stacks and stacks of cards with individual bits of knowledge scribbled on them that we felt were essential knowledge (here’s the proof on Flickr). This start, and the following process of sorting through our “ideal” requirements based on time constraints, were the seeds for all of the work that followed. Our group spent the semester developing classes, curriculum, reviews, assignments, syllabi, grade sheets, critiques, and any other minutiae that goes into creating an entire sequence of classes that make up a design program. Essentially, we conceived, developed, and implemented a design program, from scratch. The fact that I loved the process—that it felt more like fun than work, further cemented the fact that I was made to be an educator. Talk about confirmation!

The experience demonstrated the amount of planning and care that goes into shaping future graphic designers. It’s an important but daunting task. The semester also highlighted the sobering fact that there’s so much to teach and so little time. This is only exacerbated by the fact that legislatures are beginning to limit the number of hours that can be required for degrees (a Bachelor of Fine Arts in this case) in an effort to get students through college faster and cheaper. My experience revealed this: one cannot hope to build in all of the conceptual repetition, process practice, skills knowledge, cultural awareness, historical research, technological prowess, and business acumen required of a practicing designer into a design program. It would take forever! So, you do your best to create a curriculum that teaches what the student needs most, and you build into them the awareness of the areas where they need to grow and you encourage that hunger for growing themselves after they graduate.

For me, it confirmed my thoughts on the core of excellent design education: to teach concepts, not software skills.

Aha!

Learning how to teach is just as important as learning what you’re teaching.

University Citizenship and Tenure in Design

Keith Owens

Academia is a strange land. The customs are foreign, the history is maligned, the purpose is debated, the governance is peculiar, the language is esoteric, and the culture is unlike anything in the rest of the world of employment. University Citizenship and Tenure in Design was created to help graduates navigate within academia’s borders and, like Design Pedagogy, I believe the information presented in it was invaluable. To dare emulate Mr. T, I pity the fools who go into higher education and don’t have the benefit of the map of academia this class renders.

Much of this course was dedicated to self-examination. I formulated my Design Philosophy and my Teaching Philosophy, then researched and evaluated schools and departments that aligned with my personal beliefs and aspirations. The class was also tasked with examining design departments on not just their reputations, but also their geographic locations, histories, budgets, politics, and structure. I even interviewed faculty at a few schools, which rendered valuable answers that offered “boots on the ground” stories of what it is like to work in such places. Adding a rare layer of transparency to the study of academia, no topic was off-topic with my professor: our class discussed salaries, raises, sexual harassment, interviewing, firing, personal clashes, benefits, sabbaticals, among other topics, all through the lens of experience.

But there was also a great deal of study of the academy in general. I learned about the history of higher education, the reasons for tenure and we discussed its future. Through reading and discussing George Dennis O’Brien’s All the Essential Half-Truths about Higher Education, I was exposed to the foundations of the academy (and to the cracks in that same foundation) and as a result, have a better understanding of the university’s place in our society and also of the place of the educators within the academy.

In all, the experience was eye-opening and course-adjusting. I feel I have a much clearer view of what to expect outside of the classroom, thanks to this class.

Aha!

Accepting a job offer to teach is a holistic decision: teaching in higher education is more like a marriage than a job.

Seminar in 20th and 21st Century Art

Dr. Jennifer Way

I hadn’t taken an art history course in 13 years before this semester. I was bracing for what I remembered of my art history survey courses: slides, dates, titles, and regurgitation. But instead, I got theory, discussion, interaction, and relevant application. Art history has changed a lot, and I like it.

The topics in this course change regularly and spring 2011’s content was focused on the relationship between Modernism and Modernity. I’ll let you explore more on the topic (as I could write thousands of words on it) but in a nutshell, modernity is the cultural condition where constant innovation and progress (often through technology) become a primary driving force in thought, practice, and in beliefs. Modernism (a la Modern Art) is generally considered to be the art that was produced somewhere between 1900 and the 1960s that reacted to and reflected the condition of modernity. One overarching theme in the class for me was that when one considers the generally accepted definition of Modernity, there is a pretty good argument that can be posed that we are still in Modern times, despite the claim that the art being created today is Postmodern.

For our semester-long assignment, the class divvied up movements and periods of Modernism and was tasked with creating a week’s worth of curriculum to teach that content as part of an undergraduate art history class on Modernism and Modernity. Over the course of the semester, I explored the art of the 19030s and 1940s in America in the process of developing a curriculum to teach the period. Through the experience my perspective of the period was broadened: I began to examine the art as a representation of the history, the culture, and as not just the personal voice of the artist, but as an expression of the nation and what was taking place in the pre-World War II period. I had never looked at art this way before. In fact, it challenged me to consider why we study history, which spawned a blog post of the same name that I posted a few months ago. The class challenged me that the study of art is not limited to just formal art, but must include the culture, politics, economics, attitudes, and general history of the period where that art was created. For me, it elevated art to where it should be: a force of reporting and expression that is a key component of the identity of the culture (not just fine arts culture).

All of this was facilitated through the exercise of the creation of the curriculum. I believe the saying goes something like: if you want to really learn something, teach it. This approach worked for me through this class and it filled me with ideas and attitudes on the period that I had never before considered.

Aha!

The advance of technology affects everything.

Up Next

I’m ready for the summer, but not ready to let go of learning. I am wrapping up work on one research project for KERA, am starting work on another research project at Cook Children’s Hospital in Fort Worth with other Grad Students and my professors, will be writing papers to submit for conferences and publications, and will be taking a class in the last summer session which will wrap up my required study in Anthropology.

It seems Depeche Mode said it best: I just can’t get enough, I just can’t get enough…

Be the First to Comment